Are Works Produced Under the Public Works of Art Project Considered Works for Hire?

This painting, The Timber Bucker, is 1 of a series documenting life in Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps completed by Washington State creative person Ernest Norling for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) during the Smashing Depression. Norling was one of roughly 50 Washingtonians and more than 3,000 Americans who participated in the PWAP, the beginning big scale regime-sponsored art initiative during the 1930'south. (Courtesy Smithsonian American Fine art Museum)On December 8, 1933, the Federal Authorities launched the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), the first of what would eventually be a series of programs aimed at both promoting the visual arts in public spaces and supporting unemployed artists during the grim years of the Smashing Low. Though information technology only lasted a cursory six months, the PWAP withal enjoyed an outsize influence on the American cultural landscape, fundamentally re-orienting the relationship of artists to government and of art to the boilerplate American. In June 1934, for example, a Seattle Daily Times article commented that, "in the futurity's estimate of the New Deal, possibly no one effort of amelioration volition prove more interesting and more revolutionary in its cultural effects than the Public Works of Art Project." [1]

Never before had the government subsidized the arts to such a degree, employing thousands of artists, including upwardly of 50 in Washington State, at wages of $38 - $46.50/calendar week, to produce over 400 murals, 6,800 easel paintings, 650 sculptures and two,600 impress designs, among other accomplishments. [2] The PWAP demonstrated that culture could found work and that those active in the cultural industries were, by extension, worthy of public support. By creating the program, the Roosevelt Assistants, in the words of PWAP Managing director Edward Bruce, "recognized that the artist, like the laborer, capitalist and office worker, eats, drinks and has a family, and pays rent, thus contradicting the former superstition that the painter and the sculptor live in attics and exist on inspiration." [3]

The idea backside the PWAP, every bit well equally later on New Deal visual arts programs, came from United mexican states. In 1922, the Mexican federal government under General Álvaro Obregón began hiring artists, including Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, to paint murals in public buildings, with the goal of promoting nationalism and social cohesion in the wake of the long and fierce (roughly 1910-1920) revolutionary period. Edifice on the traditions of Aztec painters, the muralists used fresco techniques beginning discovered through archaeological piece of work at Teotihuacán, among the near pregnant indigenous historical sites in the Americas. [iv]

Though short-lived, the Mexican mural program caught the attention of a number of American artists and intellectuals, who lived in Mexico during the late 1920's and early 1930's. Among those who studied the fresco techniques were 3 prominent artists from the Pacific Northwest: Ambrose Patterson, Marker Tobey and Kenneth Callahan, all of whom would later participate in 1 course or another in the New Deal visual arts programs. [5] The Mexican mural program likewise had an impact on some other visiting American, George Biddle. The son of a prominent Philadelphia family unit, Biddle attended boarding schoolhouse at Groton University in Connecticut before inbound Harvard University. It was at Groton where he met and became friends with the future president Franklin D. Roosevelt, a relationship that proved critical to the early on history of the PWAP.

In May 1933, Biddle, a well-known artist in his own right, wrote a now famous "Dear Franklin" alphabetic character to the recently elected Roosevelt, urging him to create a new program, modeled on the Mexican instance, which would pay painters and other artists at "plumber'due south wages" to decorate government buildings throughout the country. [6] Not only would the initiative create jobs, it would likewise provide an opportunity, Biddle noted to Roosevelt, for artists to stand for "the social ideals you lot are struggling to attain." [7] Indeed, he went on to say, a Mexican-manner plan "could shortly result, for the first time in our history, in a vital national expression." [viii]

The President was intrigued. "It is very delightful to hear from you and I am interested in your proposition in regard to the expression of modern art through mural paintings," he wrote. [9] All the same, Roosevelt likewise harbored "grave doubts concerning the political consequences of authorities supporting fine art for its ain sake." [x] Just how politically radical would the artists exist and how might their work affect the public's perception of the New Deal and, by extension, the President himself? This tension, between the politics of fine art and the art of politics, proved particularly thorny, troubling all the New Deal cultural programs, in theater, writing, music and the visual arts, throughout the duration of the Keen Depression. In the end, Roosevelt set aside his qualms (for the time being) and referred Biddle to Lawrence W. Robert, Jr. an official with the Treasury Section, who, with the assist of Eleanor Roosevelt and other New Dealers, chop-chop organized the Advisory Committee to the Treasury on Fine Arts – a new body charged with assisting the nation's artists. [11]

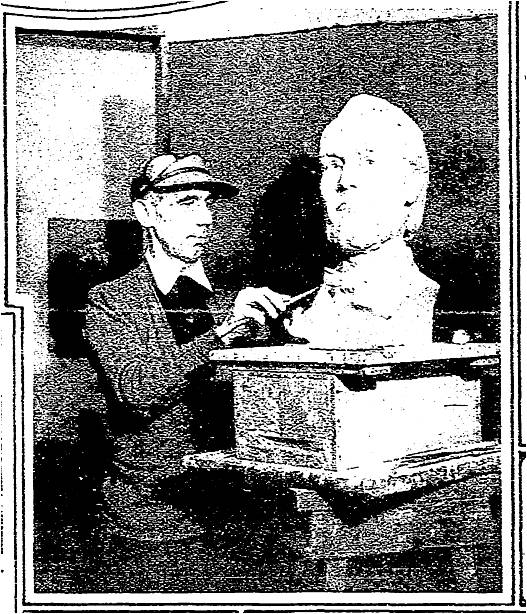

In this image, from the March 4, 1934, edition of the Seattle Daily Times, PWAP Sculptor James Wehn is pictured working on a bust of Dr. David "Doctor" Maynard, Seattle'southward commencement physician, who arrived in the area in 1852. History proved a popular theme for PWAP works, which sought to celebrate the people and story of the United States during the grim days of the Great Low. On Dec 8, 1933, just a few short months after Biddle's letter and the establishment of the Advisory Committee, Harry Hopkins, one of Roosevelt's closest advisors and the director of the Ceremonious Works Administration (CWA), announced that over $1 million in CWA monies would go to support artists under the auspices of a new Treasury Section-administered program – the PWAP. Hopkins himself had been an early supporter of the thought and probable played a role in shepherding it through the blessing process. [12] Edward Bruce, a lawyer, Treasury Section official and established creative person, became the PWAP Director, with Forbes Watson, an art critic, named Technical Advisor and Edward Rowan, as Assistant Director. All iii men believed strongly in the value of publicly funded art and advocated on behalf of the program in Washington, D.C.

The PWAP divided the country into sixteen regions, each with a director and a volunteer commission that impartially selected and employed artists. Project gear up-up took place quickly; indeed, by January 1934, over 1,400 artists and 27 laborers were already at piece of work. [13] Employment and pay structures matched the CWA more than generally, which translated into a higher and simpler wage structure than the one adult in later on years for the Federal Fine art Projection. [fourteen]

During its vi months of functioning, the project employed some 3,700 artists, allocated according to each region's population. Active in all fifty states, these men and women completed more than than 15,600 works of art, which were visible in federal, land and municipal buildings as well as parks and museums. In addition, the artists as well documented important federal initiatives so underway, including the Civilian Conservation Corps and the construction of large public works, like the Boulder Dam. [fifteen] Not but did the PWAP provide piece of work, it also restored self-respect and confidence to artists. The words of one creative person to Director Bruce capture the sentiment, "I have a new outlook on life…a future that looked so dark and hopeless simply a short while agone has inverse completely." [xvi]

Washington Land, Oregon, Idaho and Montana comprised the Pacific Northwest region, with the largest share of artists allotted to the Evergreen State. [17] Burt Brown Barker served every bit Chairman of the area'due south volunteer oversight commission. A Portland resident, Barker was managing director of the Portland Art Association and the Vice President of the University of Oregon. He was optimistic for the Pacific Northwest's potential output, noting in a Jan 7, 1934, Seattle Daily Times article, "Because our mount scenery is and then vastly different from annihilation in the Midwest, I believe the work produced here will exist exchanged with other parts of the country, although that is a part of the program not yet fully developed." [18]

In the same 1934 slice, Barker also emphasized the PWAP'due south dual – and at times conflicting – purposes. While fundamentally a relief endeavour, the program's leadership, including administrators in Washington, D.C. and many regional officials like Barker, also hoped to enhance the nation'due south cultural sensation through exposure to loftier quality art, which sometimes resulted in loftier-profile artists receiving commissions, while impoverished, bottom-known individuals languished out of piece of work. [19]

In June 1934, a Seattle Daily Times article commented that, "in the future's estimate of the New Deal, possibly no one effort of amelioration volition testify more interesting and more revolutionary in its cultural furnishings than the Public Works of Art Project." In fact, the PWAP did prove path-breaking, setting a new precedent for the relationship of government to the arts in the U.s.a..A rigorous screening process overseen past volunteer committees sought to yield first-rate, authentically "American" works that contributed to building the country'due south shared ethos and identity, much similar the Mexican landscape initiative of the 1920's. [20] These sentiments echoed ideas expressed by Managing director Edward Bruce, who commented: Nosotros live in a heterogeneous country…But when the farmer, and the laborer, the village children and the storekeepers go to the nearest post office and encounter there, for example, a distinguished work of contemporary fine art depicting the main activities, or some notable events in the history of their own boondocks, is it as well much exaggeration to suggest that their interest will exist increased and their imagination stirred? [21]

In Washington Land, approximately 50 artists participated in the PWAP during its brief tenure. For the near part, their work conformed to the aesthetic and thematic forms of the "American Scene." This movement stressed "regional and small town life and produced views of local colour and straightforward celebrations of ideals such every bit customs, democracy and difficult work." [22] It was also not-controversial and hands understood by diverse viewers unfamiliar with modern or abstract fine art.

Strict adherence to this approach was never required, but information technology did go dominant within the PWAP and to a lesser extent the Federal Fine art Project that followed. Banana Director Edward Rowan, for instance, commented that if an creative person did have the "imagination and vision to run into the beauty and the possibility for aesthetic expression in the subject matter of his own country," he or she non be considered for the program. [23] Such attitudes created rifts with many artists and art critics, who preferred more experimental methods and field of study matter. It as well acquired issues for politically active artists, whose work challenged celebratory history and patriotic storylines.

In the plan's concluding month, June 1934, a Seattle Daily Times article celebrated the achievements of Washington State artists. In particular, the paper highlighted the completion of 2 large, carved, cedar bas-relief bound for local schools. The first, some x feet long and 3 feet high, by Marion "Ivan" Kelez, depicted the landing of Arthur Denny's Political party at Alki Point in what is now Due west Seattle on November 13, 1851. Amongst the get-go Euro-Americans to settle permanently in the region, the Denny Political party served every bit a powerful and romantic symbol of the Pacific Northwest's not so distant past. Inscribed on the panel was a quote from Roberta Frye Watt, the granddaughter of Arthur Denny: "Surely, nosotros owe these pioneers — those pilgrims of ours a debt of gratitude. Oh, speak not lightly, the discussion 'pioneer' but gratefully, lovingly, reverently." [24]

The bas-relief likewise referenced the indigenous peoples who were living in their ancestral homelands along the shores of Puget Sound when the Denny Party arrived. In addition to the presence of a Native fisherman in the corner of the scene, there is besides a quote, attributed to Master Seattle (or si?al in his native Lushootseed language) of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes, that reads: "When your children's children think themselves alone in the field, the store, the store, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they volition not be solitary. At dark when the streets of your cities and villages are silent and you call back them deserted, they volition notwithstanding throng with the returning hosts that in one case filled them and all the same dearest this beautiful land. The white human will never be alone." [25]

Less detail is available on the 2nd bas-relief, which, the Seattle Daily Times reported, envisioned the "coming together of boys and girls of all nations to make the platonic high school civilisation, to be placed in the entry mode of a particularly cosmopolitan schoolhouse." [26] These subjects, a romanticized pioneer past and an almost utopian, egalitarian present and future, historic mainstream ideas of American idealism, hard work and perseverance at a moment of extreme national distress. The panels, which were past no means unique in their approach, offered viewers a vision of hope and unity amongst the economic and social turmoil of the Depression. They sought to re-assert an - at times - wavering organized religion in the possibilities of liberalism, American exceptionalism and industrial capitalism, while downplaying or ignoring the frequently painful complexities of the nation'south past, such as violence and discrimination confronting Native peoples.

Other works produced in Washington State nether the auspices PWAP included: murals in the Women's Recreation Building and the Oceanographic Building at the University of Washington; an all-encompassing marine life diorama for the Academy Museum; paintings in a Seattle senior citizens home; fe gates for a memorial gateway to the south park playfield in Seattle; samples of early American weaving from the southern and eastern United States for the state school system; wood carvings of mountains and other nature scenes by a "young Norwegian" in Tacoma; and plant nursery school-themed art for government-run daycare centers.

This painting, Wheelbarrow, by Morris Graves, was completed equally part of the Public Works of Art Projection in 1934. Photo courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum (Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Pacific Northwest artists active in the PWAP likewise received national recognition for their work, highlighted by the inclusion of 15 Washington State artists, including Morriss Graves, who would gain acclaim as a fellow member of the Northwest School, in a 1934 exhibit at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington D.C. After reviewing the prove, President and Mrs. Roosevelt selected a handful of works to hang in the White Business firm. Among those chosen was "The Timber Bucker," a painting past Seattle artists Ernest Norling, which depicted life in the state's CCC Camps. [27] Other works, not sent to Washington D.C., went on exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum during the leap and summer of 1934.

In a 1964 oral history interview, Norling remembered his time on the PWAP documenting the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. "The piece of work was every interesting, " he recalled. "I went out to Parkers Island to the army camp which is now Omerand State Park and in that location were at least 200 boys there and they were building a route upward to the top of Mount Constitution. I fabricated sketches of this work that they were doing. They were very interested in anything mechanical. They could accept two men on a crosscut saw and saw a log off in five minutes merely they would work an hr or two on a power saw to get information technology going, to – you lot know how they... But, they were squeamish boys. We went upwards on the Hood Canal projection and that was much the aforementioned. They were road building and improving the surface area there. And following that came the mural project." [28]

During a brief six months, the Public Works of Art Program managed to upend many long held notions of the proper relationship between government and the arts in the Us. Rather than rely solely on private patronage, which had largely dried up during the Great Depression, artists could at present look to the government equally a partner and a sponsor of their work. In return, artists dealt largely with themes "American" in nature, depicting places, people and stories familiar to the population at big. PWAP administrator Forbes Watson, who went on to play a part in other New Bargain arts initiatives, summarized the program's bear upon equally follows:

"Before 1933…we had a large, groping, hungry public which looked to fine art every bit a means whereby its tillage and outlook on life could be broadened. This was a public which, thanks to its idealistic optimism, did not realize the facts about the artist. Suddenly a country which more often than not speaking wanted to be tenderly cultivated without buying was transformed into a country which overnight became the largest purchaser of art in the making that the earth has ever known." [29]

Copyright (c) 2012, Eleanor Mahoney

[ane] Margaret Prosser, "Needy Artists Profoundly Aided by Regime," Seattle Daily Times, June 17, 1934, p.8.

[ii] Bruce Bustard, A New Bargain for the Arts (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Assistants in clan with the University of Washington Printing, 1997),half dozen.

[three] Judith Chiliad. Keyser, The New Deal Murals in Washington State: Advice and Popular Democracy, Thesis (M.A.)--University of Washington, 1982), 39.

[four] Keyser, 32-33.

[5] Ibid., 35-36.

[6] Bustard, 4.

[7] Ibid, iv.

[8] Keyser, 37.

[9] William Francis McDonald, Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration. (Columbus: Ohio Country University Press, 1969), 358.

[ten] Keyser, 37.

[11] Martin R. Kalfatovic, The New Deal Fine Arts Projects: A Bibliography, 1933-1992 (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1994) , xxiii.

[12] Keyser, 38.

[13] McDonald, 364.

[14] Ibid., 364.

[xv] Ibid., 365.

[16] Bustard, half-dozen.

[17] According to Baker, the largest share of the regional money had been set bated for Washington Land, as "the regional art committee feels its artists are capable of producing the largest amount of acceptable work," from "American Art to be Given Impetus by C.Westward.A. Plan," Seattle Daily Times, January seven, 1934, p.four.

[18] Ibid.

[nineteen] Ibid. On this detail upshot and the controversy information technology sometimes caused encounter McDonald, 366-367.

[20] Keyser, 39-43.

[21] Ibid, 40.

[22] Bustard, 24

[23] Such controversies, however, did not impact the program in the Pacific Northwest region. More often than not well received, the PWAP generated far less controversy or consternation on the political right and the left than the Federal One Programs (Theater, Fine art, Writing and Music).There were certainly criticisms, especially from those that felt that radicals controlled the plan, only the presence of Edward Bruce, a conservative equally Director, helped to quell such critiques.

[24] Sanjay Bhatt, "Alki Elementary'due south Celebrated Landscape in Demand of TLC," Seattle Times, Jan i, 2005, accessed August xx, 2012, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2002137505_alki01m.html.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Prosser, 8.

[27] Ibid. Keyser, 65.

[28] Oral history interview with Ernest Ralph Norling, 1964 Oct. 30, Archives of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution, accessed Baronial 19, 2012, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ernest-ralph-norling-13113.

[29] McDonald, 368.

Source: https://depts.washington.edu/depress/PWAP.shtml

0 Response to "Are Works Produced Under the Public Works of Art Project Considered Works for Hire?"

Post a Comment